politics & conflict

The decades of civil and political unrest in Northern Ireland were marked by deep division, violence, and political strife.

Back to ExhibitionA Contested History

The legacy of the Troubles is still contested, with multiple narratives vying for recognition. There is no single, agreed-upon version of events, and this exhibition embraces that complexity.

Rather than seek consensus, we aim to curate diverse perspectives, placing voices from all sides of the conflict into conversation with one another.

Politics on the Streets and Beyond

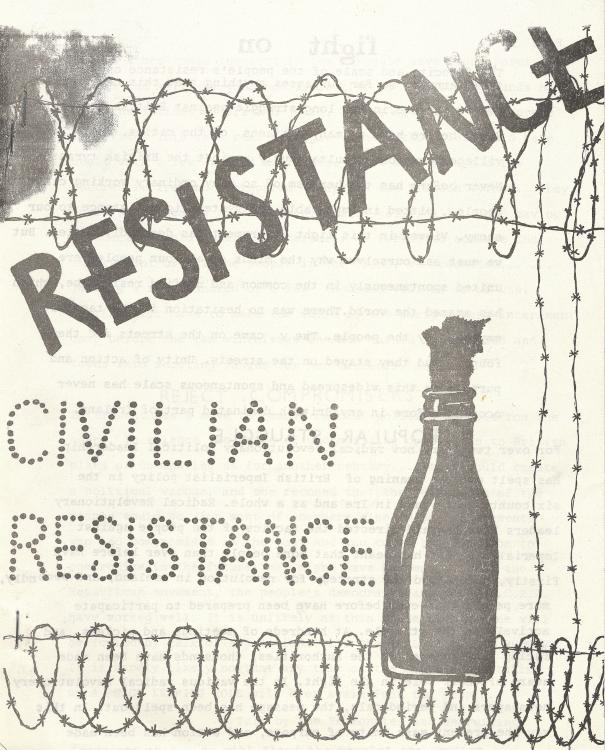

At the heart of this theme is the undeniable connection between traditional politics and street-level activism. Political decisions and power struggles in government corridors were deeply intertwined with the actions taking place on the ground. As violence escalated, the lines between political debate and armed conflict became increasingly blurred, with each arena fueling the other.

One key moment of political fragmentation occurred in 1973, when a faction of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) broke away to form the Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party, led by William Craig. This split arose after the UUP failed to oppose British government proposals for enforced power-sharing and a political relationship with the Republic of Ireland. Such events highlight the intense political disagreements within unionism itself, reflecting how political maneuvering was often accompanied by heightened tensions and violent consequences in the streets.

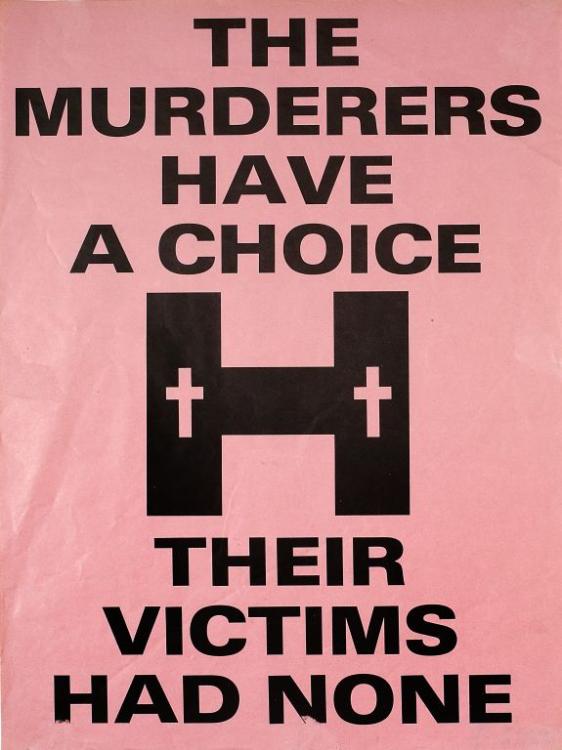

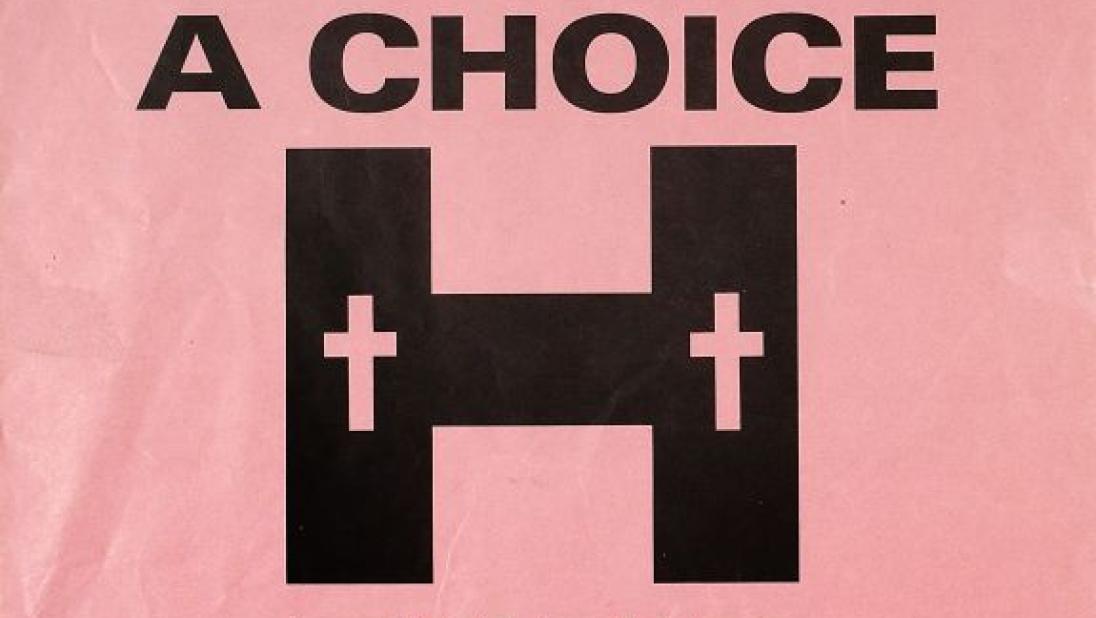

The story of Bobby Sands, elected as an MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone in 1981 during his hunger strike, is one of the most powerful symbols of the intersection between politics and conflict. Sands' election as an Anti H-Block candidate occurred just weeks before his death, and his story resonated deeply with communities across Northern Ireland, both as a political act and a stark reminder of the human toll of the Troubles.

Women and the Hidden Toll of Conflict

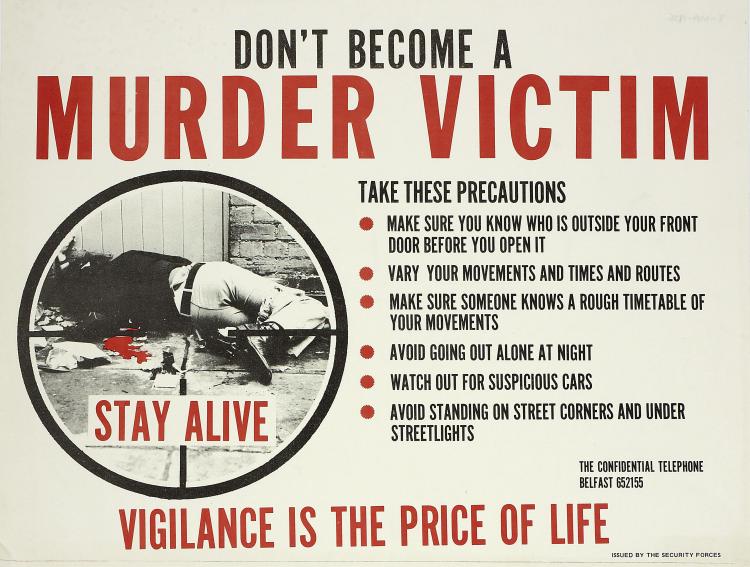

While much of the violence during the Troubles was perpetrated by men—around 90% of the fatalities were male—the impact on women was profound, albeit often less visible. Women’s roles during this time extended far beyond the battlefield or the political stage. Many bore the burden of maintaining households where family members had been killed, injured, or imprisoned. With approximately 300,000 house searches conducted in the early 1970s alone, women often found themselves at the center of political violence, managing the emotional and logistical challenges of conflict in deeply personal, domestic settings.

Some women chose to step into the political sphere, actively campaigning for peace and advocating for change. Others became victims themselves, but the stories of their resilience and the ways they were affected by—and responded to—the violence around them are critical to understanding the full picture of the Troubles.

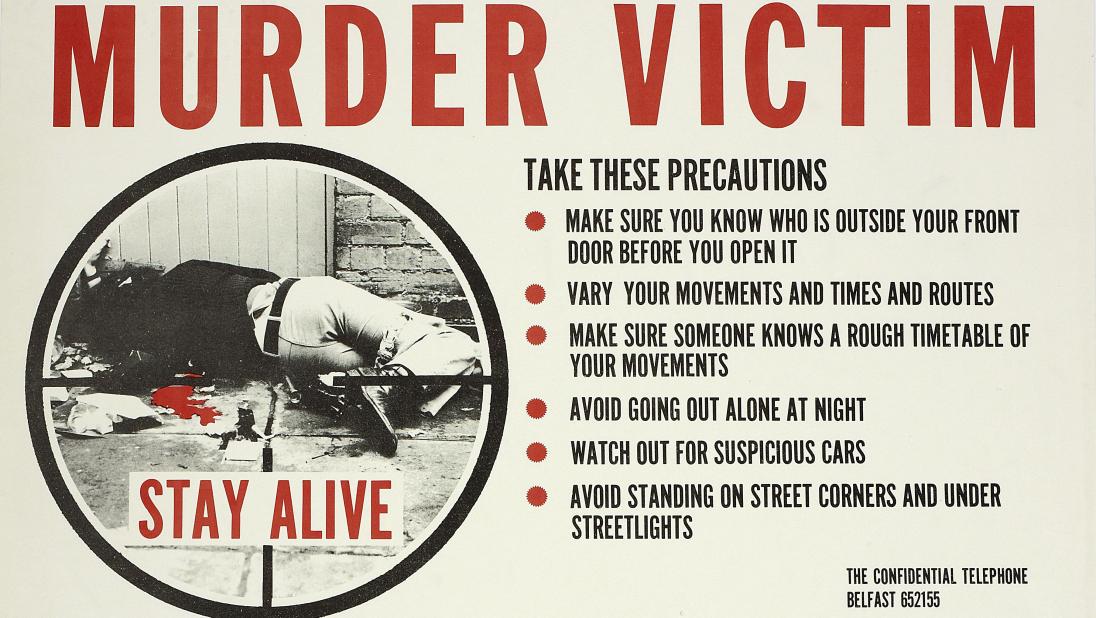

Local Impact and Legacy

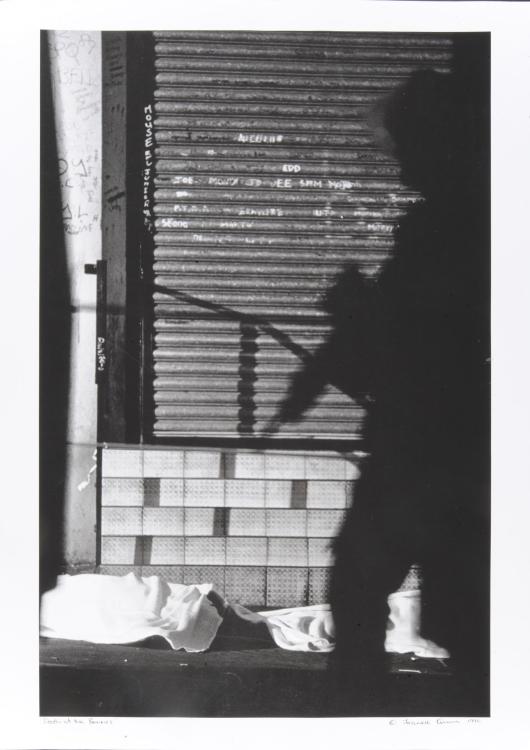

Violence was not only felt in large political arenas but often in intensely local settings. Roughly one-third of all killings in Belfast, for example, occurred within or near people’s homes. These localised experiences of violence created deeply sensitised communities, where fear and trauma were woven into the fabric of daily life. In neighborhoods across Northern Ireland, people lived in a constant state of awareness, where the next attack could come from close by. This localised dimension of political conflict ensured that its legacy would be long-lasting, particularly in the most affected communities.